A reflection by Peter Noordhoek on Ella Al-Shamahi’s ‘The Handshake. A Gripping History. Profile books, 2021′.

What is the secret of a handshake? Why was the handshake so logical pre-Covid and why are we still searching for the right alternative as we are slowly leaving the pandemic behind? In a recent book, the scientist and comedian Ella Al-Shamahi argues that it is much too early to say goodbye to the handshake post-Covid. She gives many good reasons why, and also debunks the reason why we shake hands ‘in order to show that the empty hand shows we carry no weapon’ (in fact it is not unusual to shake hands while showing weapons).

It is a great read, but reading it, I was waiting too long for one specific reason how and why we might shake hands, so maybe there is something to be added to the book or expand on this aspect more. I do so as someone who, as a trainer, has for the past ten years or so started most of my training sessions by drawing attention to the role of the hand in communication. As I have done so with more than a thousand participants and across borders and cultures, I might have something worthwhile to say about it.

Starting a meeting in and after Covid time

Last week was the first time I was so fortunate to train a group ‘live’, in each other’s physical presence. A distance of at least 1,5 meter was still to be observed. Even more than I used to do, I observed closely every participant entering the room. It was a strange mix of greetings, or lack of them. Elbows were used, voices were used loudly in greeting. Some, like me, laid a hand on the heart. Several did nothing and just sat down and looked straight ahead, as if they were starting a session of Teams or Zoom. I noticed some extra nervousness on my own side, as I am used to firmly greet each and every participant coming into the training room with a handshake, even the latecomers. Apart from basic civility, there is a reason for that, as I will explain.

Starting a campaign

Politics in the Netherlands is mostly a volunteer activity, though you often bring to it your own professional background, knowledge and skills. As a trainer by profession, it is often through educational activities that I support my political activities. This is also how I approach election campaigns. Over the years, I have participated in dozens of campaigns, 17 of them as a campaign leader. Campaigning is fundamentally a group activity. For a political party it is one of the best and most exciting ways of getting older party members energized again and young people involved. I like to get all people involved together at an event. In fact, several events at different times, but certainly at the beginning. From lead candidate to flyer distributers, everybody has a role to play. But I was not always satisfied with the way these events went. Participants were talked to, reduced to the role of listeners. Too much information, not enough action. Too much strategizing, not enough practicing. How to change that? Then I got an idea that I am still stuck with up to the present day.

What happens at the start?

At the beginning of an event, I once started out by asking questions like: “What happens at the start of each campaign?” of “What is at the heart of every campaign?” I am still asking this question today and always get loads of rational answers, but nobody comes up with this one: “You shake hands”. As simple and informal as it sounds, you could very well say that shaking hands is both the start and the goal of every campaign. At the beginning of an event, but also at the door of constituent or a meeting on the street. Shaking hands with as many voters as possible, is the holy grail of campaigning (which can easily be followed up-by stories and techniques of politicians shaking hand (Al-Shamahi does this well, though she misses the wonderful story about Bill Clinton’s technique of shaking hands. It is great fun to practice it with participants.). Meanwhile, I ask all participants to stand up and shake the hands of the people standing next to them. I ask them “How was it?”. Some people then respond by saying things like “firm”, “Okay” or “good”. (At this point I sometimes ask them if they remember the handshake I gave each when coming in. Many do not, at first).

Hi, would you vote for me?

Then I ask them to remain standing and turn to the person next to them, give him or her a handshake, at the same time asking this: “Hi, I am (name). Would you vote for me?” Now the room gets loud. You hear many times “Yes”, hardly anyone daring to say “No.” People get in the mood, but there’s another question coming: “Do the same. Give your name, ask for a vote, but do so while slowly going through your knees.” What? I usually have to ask two participants to demonstrate this for the group, after I have showed them how. Then all of them accept the assignment, obviously feeling like fools. But what they almost all always do, is to somehow mirror each other’s movement, with both the one asking for the vote, and the voter, going through their knees, and keeping eye contact.

Having asked them this, with everyone more or less out of their comfort zone, there is not a single one not aware of how the other person shakes hands. And how they themselves shake hands. I will use this awareness later on, when discussing different tactics to get in touch with voters. But first it is time to restore order and ask this question: “Why do we shake hands?” This may again result in different answers, but now there is one answer that comes logically to the forefront: “In order to look each other in the eye.” And this I confirm, or if it that answer still has not come up, I ask, meanwhile trying to stand on one leg, “Why do we not greet by touching feet?”, and then the answer is the logical one: because the hand guides the eyes, and the hands are

Matching the speed of our brains

We all have this enormously smart brains. They are still faster than any computer can manage, helping us to make judgements about other people, literally in the blink of an eye. And on the whole, we do this well even though we can never fully trust that judgement. In trainings I do for auditors, in line with authors like Malcolm Gladwell, I say you can probably write your report about an office with 80% accuracy just after the handshake and your blink of the eye. So, I say to those fresh auditors; relax, and take the rest of the day to test your assumptions. With campaigns it is different. With thousands of voters to convince of your good intentions, nothing beats a few well-chosen words brought with a handshake and the meeting of the eyes by two individuals, but there are simply too many voters to meet. Most of modern campaigning is in my view now no longer aimed at meeting the voters through a mass effect like that of television or large meeting, but by mimicking the effect of a handshake through social media.

Alternatives and different cultures

Is it only possible to have this eye-to-eye contact through a handshake? No, of course not. Neither is it true that you need eye-to-eye contact to know the other person. The single handshake alone already tells a lot, mostly, as Ella Al-Shamahy tells convincingly, through smell and touch. But there is little doubt in my mind how strong the relation is between a handshake and the meeting of the eye. Just like I am convinced this is a quite universal thing, judging from what I have seen in many training sessions I did abroad. In Eastern and Central Europe, the handshake is still quite a macho thing, and you have to stimulate younger people, especially girls, to use their handshake to good effect. In the Arab world the handshake appears to be given lower, and with less meeting of the eye. Of course, there are Muslims that do not give a handshake, especially females, but among younger people and in the business communities, the differences do not seem to be too big, and if they are, the whole exercise may give rise to interesting debates about customs and culture among the participants.

It is about the eyes, not the hands

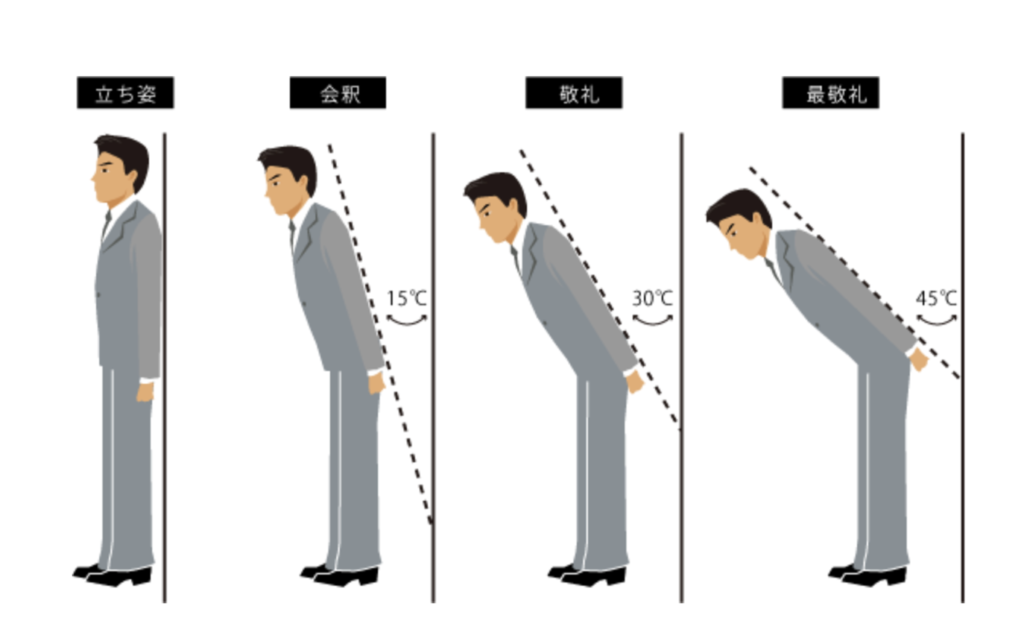

And in Asia? Well, given the restrictions of Covid, I thought it might be a good idea to use Japanese bowing as an alternative to the handshake. This worked up to a point. The Japanese (and other countries) have different degrees of bowing, depending on hierarchy and what needs to be exchanged. But the interesting thing is, that the more equal the relation, the better the eyes can meet. It is when there are differences in hierarchy, or when difficult messages have to be brought, that it gets harder and harder to meet eye to eye. It might be that the most important part of this ritual is the fact that, however short, all involved have to stand still to go through this ritual. That way a handshake is less necessary to bring the eyes together. Still, in the end it is all about the eyes, not the hands.

To conclude

I fully agree with Ella Al-Shamahi in the sense that after Covid19 the handshake will return to ordinary life (I do not hope the same for the three cheek kisses we have in the Netherlands). In my mind this, however, has less to do with culture or history or other ‘biological imperatives’, than with the easy way a handshake connects eyes to each other. To the average reader of her book this distinction may not matter much, but I thought a next version of the book might benefit from a little bit more attention to the relation with eye contact. When the eyes do not meet, no handshake or bow can really make up for that, is a way to conclude this text. or, ending on a more positive note: it is wonderful we have hands to strengthen our meeting at eye-level, but there are other ways to greet one another. Let us keep on doing so.

Dr. Peter Noordhoek is trainer, auditor, association expert and coach to politicians in the Netherlands. He works as trainer for the Eduardo Frei Foundation of the CDA, and several international institutes like KAS, IRI and NDI, in the support of democracy throughout Europe and North Africa. More of his work, also in English, can be found at www.northedge.nl. He apologizes for all his sins against the English language.